“Seeing” the World with Your Feet: Surface and ground in the work of Takayuki Mitsushima and Tomonari Nakayashiki

Sometimes, as soon as I leave the house, I have to stop to take off one of my shoes to remove something that has lodged itself in the sole. I know it’s inelegant, but the discomfort it causes prevents me from walking any further. However, I’m surprised to find that what’s lodged in my sole is often, contrary to what I imagined, much too small and delicate to be called a “foreign object.” What I’m trying to say is that the soles of our feet are really that sensitive. While this may be a personal quirk, this sensitivity is something that surprises me. And although I just now wrote “personal,” I sometimes see people in train stations and elsewhere with one hand against a pillar doing the same thing, so it’s safe to say that there are others besides myself who have experienced this same sensitivity. I have no idea where on earth this sensitivity could have come from, but after seeing this exhibition, I feel that I understand things a little better.

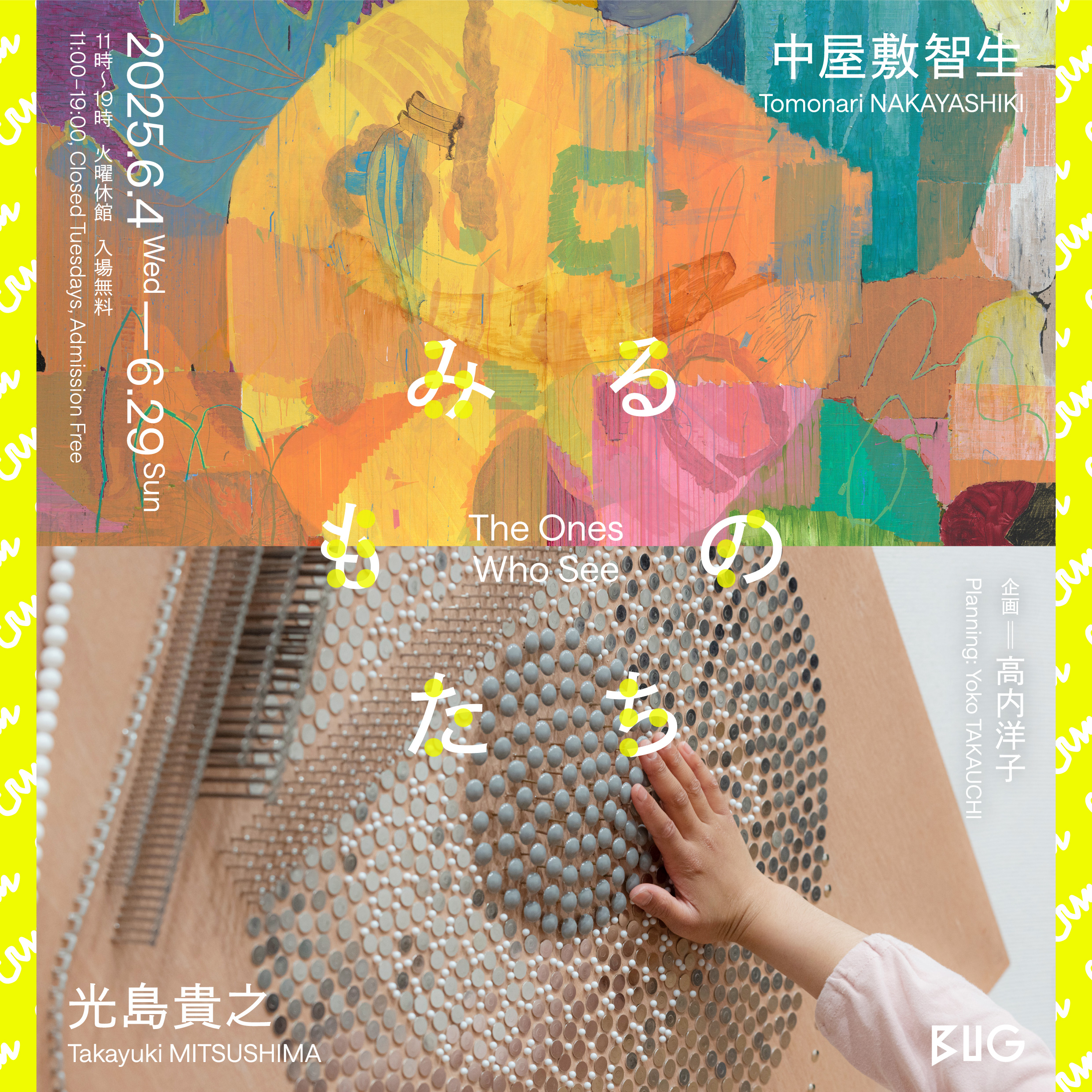

In this two-person exhibition by Takayuki Mitsushima, a blind painter, and Tomonari Nakayashiki, a painter with color-blindness, we can experience their paintings by touching them with our hands. Hearing this, I (and probably others) felt compelled to touch all of the works, and the novelty of being able to touch a painting overshadowed my experience when I first visited the gallery, leaving me unable to focus on each individual piece. A little while later, I had a student give a presentation about the exhibition in a seminar at the university where I work. The echoes of our class discussion of the show lingered with me, and I continued thinking about the show intermittently when one of those incidents from the start of this essay occurred. I realized then that while we might be able to touch the paintings with our hands, our actual experience of them as paintings would become vastly more tangible if we could engage with them with the soles of our feet (although of course such a thing is not actually allowed). Upon my second visit to the gallery, I found myself imagining this as I touched their work.

In other words, I experienced their paintings by imagining that I was touching them with the soles of my feet, when in reality I was touching them with my hands. But so what? On my first visit, I was so distracted by being able to touch something that I normally wasn’t allowed to that I never really gained a clear picture of the paintings themselves. But on this second visit, they “seemed” to be much more substantial, their contours more clearly defined. To put it another way, I replaced my hands with my feet, so that rather than touching the paintings that had been installed on the wall in front of me, I was “seeing” the paintings as if I were stepping on them on the floor and tracing the contours with my feet.

The idea of tracing the world with the soles of one’s feet isn’t really related to Mitsushima’s blindness or Nakayashiki’s color-blindness. Everyone does it. For example, I wrote at the start of this essay that I stopped immediately after leaving my house to remove something lodged in the sole of my shoe, but even putting that aside, from the moment I leave the house, my entire experience of the outside world occurs through the soles of my feet given that they are pressed against the soles of my shoes. I have functioning eyesight, so of course I “look” at the outside world. However, at the same time—or rather, beyond that—I have a continuous experience of the outside world through the soles of my feet. In contemporary society, the eyes are considered particularly important among the human sensory organs, such that we often think of “looking” with our eyes as happening just as ceaselessly—or perhaps even more so—as “seeing” the world with our feet. But the truth is that while it seems as though we’re “looking” closely at the world with our eyes, in fact we aren’t “seeing” it nearly as well as we do with the soles of our feet.

What we see with our eyes is always physically separated in some way from our current position (it is impossible for us to see something at a zero distance from ourselves), and there is no direct contact with the ground the way that there is with the soles of our feet. Furthermore, in terms of human survival, the constant, unceasing contact that the soles of our feet have with the ground gives us a much more heightened sense of reality compared to seeing something from afar. “Seeing” a bolt of lightning in the distance is not immediately life-threatening, but it could be life-threatening to take a wrong step off the stairs on which my feet are planted. In this regard, the sense of touch is far more urgent than the sense of sight. It is a kind of lifeline for us all, particularly when we step out into the world. And to reiterate, this reality and urgency of our sense of touch is basically unrelated to whether (or to what extent) the creator of a work we encounter is or isn’t visually impaired.

Of course, when we think of the sense of touch we immediately think of touching something with the palms of our hands rather than the soles of our feet—and in fact, this show does allow us to experience these paintings with the palms of our hands—but the reason I have been emphasizing the soles of the feet as I write this is because I feel they are far more adept in terms of maintaining uninterrupted contact with the world. (There are plenty of times when there is nothing in our hands, but rarely is there a moment when the soles of our feet aren’t in contact with the ground.) And if this is true, then, given conditions for “seeing” paintings like the ones in this show, I feel that it is the soles of our feet, rather than the palms of our hands, that would enable the world of these paintings to assume a level of tangibility that is “immediate” in the truest sense of the word.

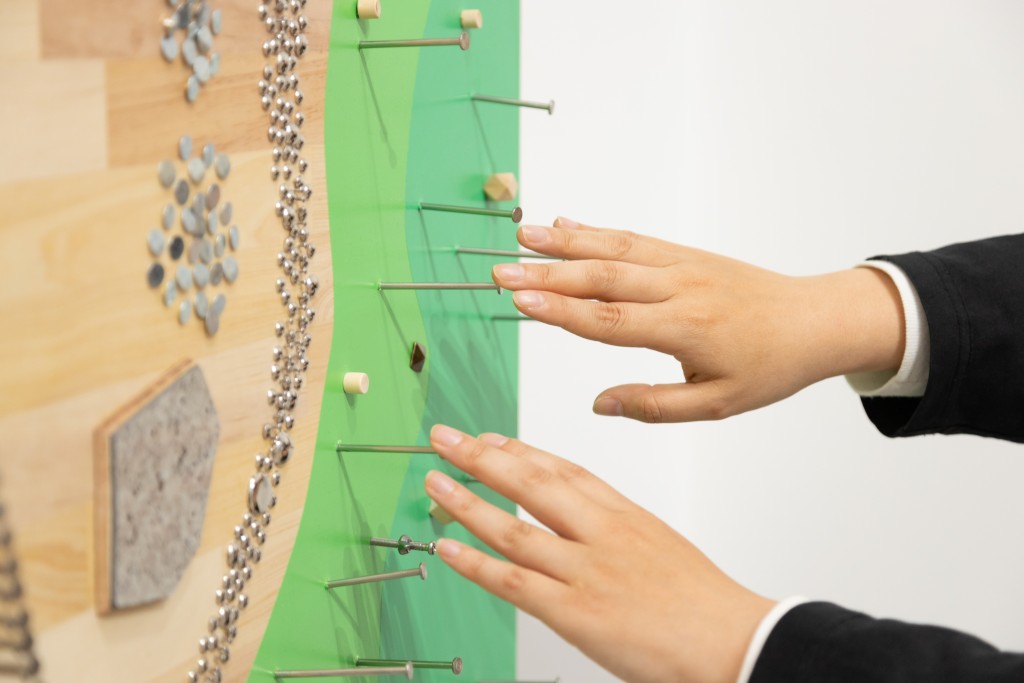

The fact is, and this is something I only confirmed later, Mitsushima’s paintings are planar depictions of his sensations while walking around his neighborhood. Because these sensations are transferred to a planar surface, the work can ultimately be hung on a wall, where it becomes possible to experience it as a painting. The ability of the viewer to touch this work, too, is in large part thanks to the format of the exhibition itself. However, Mitsushima’s recreation of elevation changes and slopes through nails imbedded in the wooden boards that serve as his canvases are based on the experiences he has of “walking” through the city with a white cane, and in this way is even more deeply connected to the idea of “seeing” the world with the soles of one’s feet. In this case, it’s certainly worth imagining what it would be like to put Mitsushima’s paintings not on a wall, but rather on the floor and “see” them by tracing the contours with our feet. In addition, once I realized that the paintings Nakayashiki produced for this show are made up of highly adhesive tape rather than paint, not only did I look at them, I touched them with my hands and retraced the experience that Nakayashiki actually had creating the painting through repeated affixation and removal of layers of tape. When I did so, I was overcome with the sensation that I was walking freely over the painting rather than just touching it.

However, it’s possible that even those of us who are open to touching paintings with our hands would probably have strongly resisted the idea of experiencing the work by stepping on it with our feet. It’s possible the creators would feel that way too. When I thought about why such a psychological resistance would occur, the word dosoku [outside shoes] immediately came to mind, along with fumi-e [tablets with Christian images on which people were forced to step] and their historical connection to psychological torture, and I realized that there’s a part of me that considers feet to be dirtier than hands. Yet thinking about it from the opposite perspective, perhaps the historical persistence of this prejudice is not unrelated to the idea that the soles of the feet are particularly sensitive parts of the human body, parts that have given us an immediate, continuous experience of the world, enabling us, moment-by-moment, to avoid life-threatening dangers. (The real danger of walking while using your phone seems to be that in constantly touching a screen with our hands as though our sense of sight were our point of contact with the world, we extinguish the sensitivity in the soles of our feet, disconnecting ourselves from the sensation of walking that is an inherent part of human self-preservation. But I digress.)

With all of this said, now, at the end of this essay, a word about why I’ve chosen to refer to Mitsushima and Nakayashiki as painters, not as artists. This is because I believe that the work Mitsushima and Nakayashiki produce is indeed painting. Painters paint by constantly touching the surface of their work with their hands. In which case touching these paintings with one’s hands, despite the various reasons why we can’t always do so, would in fact be the true nature of painting itself. Therefore, the work is a painting before it is art, and the two people who have created it are painters before they are artists.

Born in Chichibu, Saitama Prefecture. His major writings include Nihon Gendai Bijutsu [Japan, modernity, and art] (Shinchosha,1998), Sensō to Banpaku [War and the World’s Fair] (Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, 2005), Go Bijutsu Ron [Post-art theory] (winner of the Yoshida Hidekazu Prize in 2015) and Shin Bijutsu Ron [Seismic art theory] (winner of the Ministry of Education prize in the arts in 2017), both of which were published by Bijutsu Shuppan-sha, and Pandemikku to Āto 2020–2023 [Pandemic and art 2020–2023] (Sayusha, 2024) among numerous others. He has curated exhibitions such as Anōmarī [Anomaly] Roentgen Art Institute, 1991), Nihon Zero Nen [Japan Year-Zero] (Art Tower Mito, 1999-2000), Bubbles / Debris: Art of the Heisei Period 1989-2019 (Kyoto City Kyocera Museum of Art, 2021).