Where Do Characters Come From? Where Are They Going?

How have the imaginations of Japan’s children been shaped since the end of the Second World War? For example, let us look at my generation, which was born amid the economic crisis of the oil shock, following the period of growth during the Korean and Vietnam Wars referred to as the economic miracle: as children, we were all obsessed with manga and anime, we enjoyed television and magazine content, and we played baseball, soccer, and tag in vacant lots. Later, the games moved from the vacant lots to CRT TVs and LCD screens, and all kinds of gaming hardware and software grew popular. As the internet became mainstream, children’s play moved from real sites to latent-space websites. Children’s ludic bodies have always moved between real and virtual spaces.

As we grew up surrounded by mass-produced petroleum-based products, steeped from day one in brand names drilled into us by corporate advertising, what freed our imaginations were tokusatsu (special-effects-heavy) films with kaijū (monsters) and Super Sentai superhero shows, or dramatic battle scenes featuring “henshin heroes” (who can transform into more powerful incarnations). A child’s bedroom in a small ready-built house or apartment would typically contain a mix of PVC collectibles and other plastic toys for boys or girls. The gaming arcades, home video games, and small portable consoles that proliferated from the end of the 20th century introduced a new field of imagery to this history of children’s material imagination: the screen. Like an unfinished drawing, low-resolution pixel art presented an opportunity to fill the incomplete parts with one’s imagination and pour oneself into the simple battles and RPG adventures with an uninhibited mindset. Just like a mysterious theatrical space imbued with the imaginary worlds of young boys and girls, the limited nature of pixel art and the jerky movement in early video games vitalized our minds, functioning as a kind of onscreen Arte Povera (poor art).

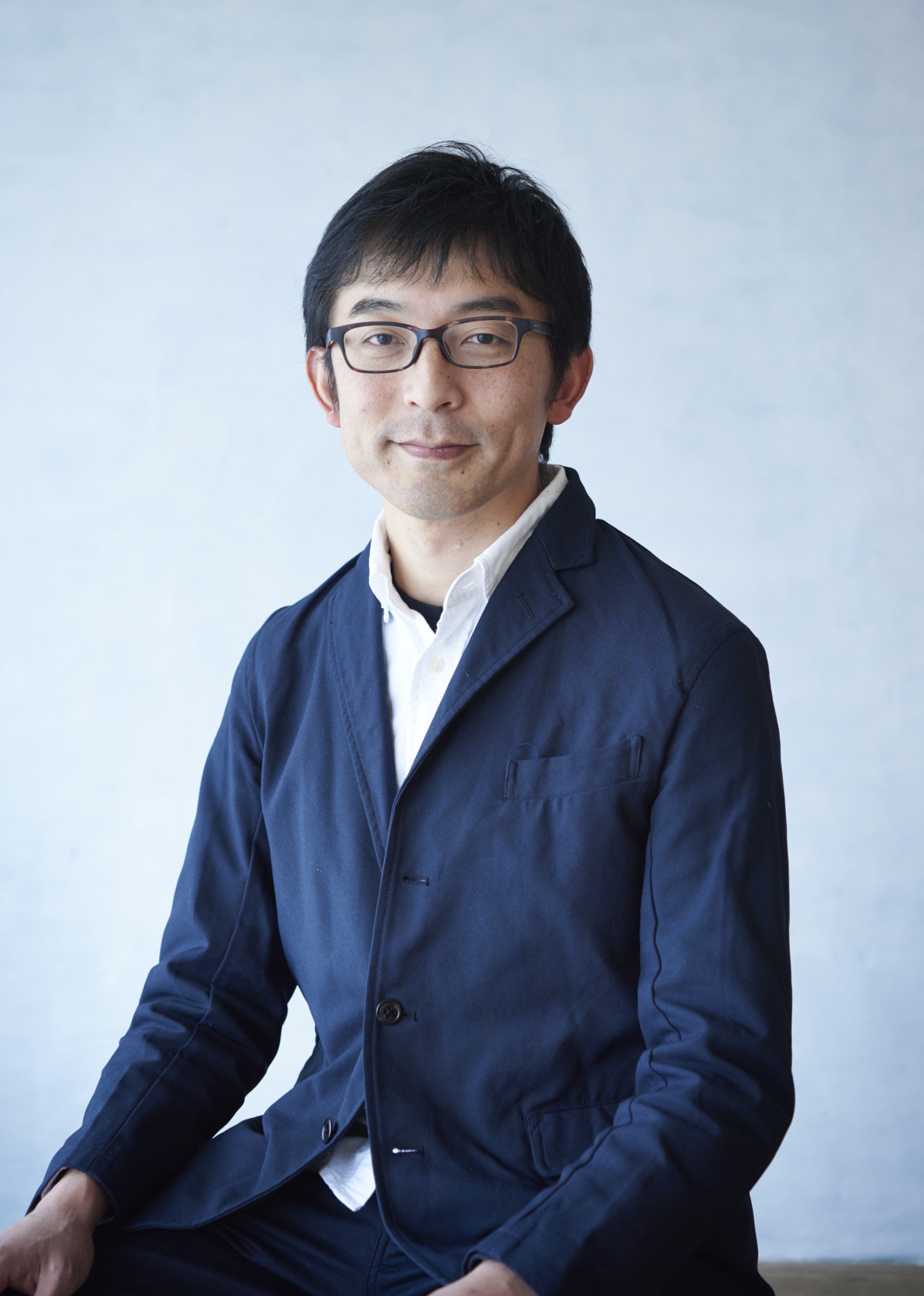

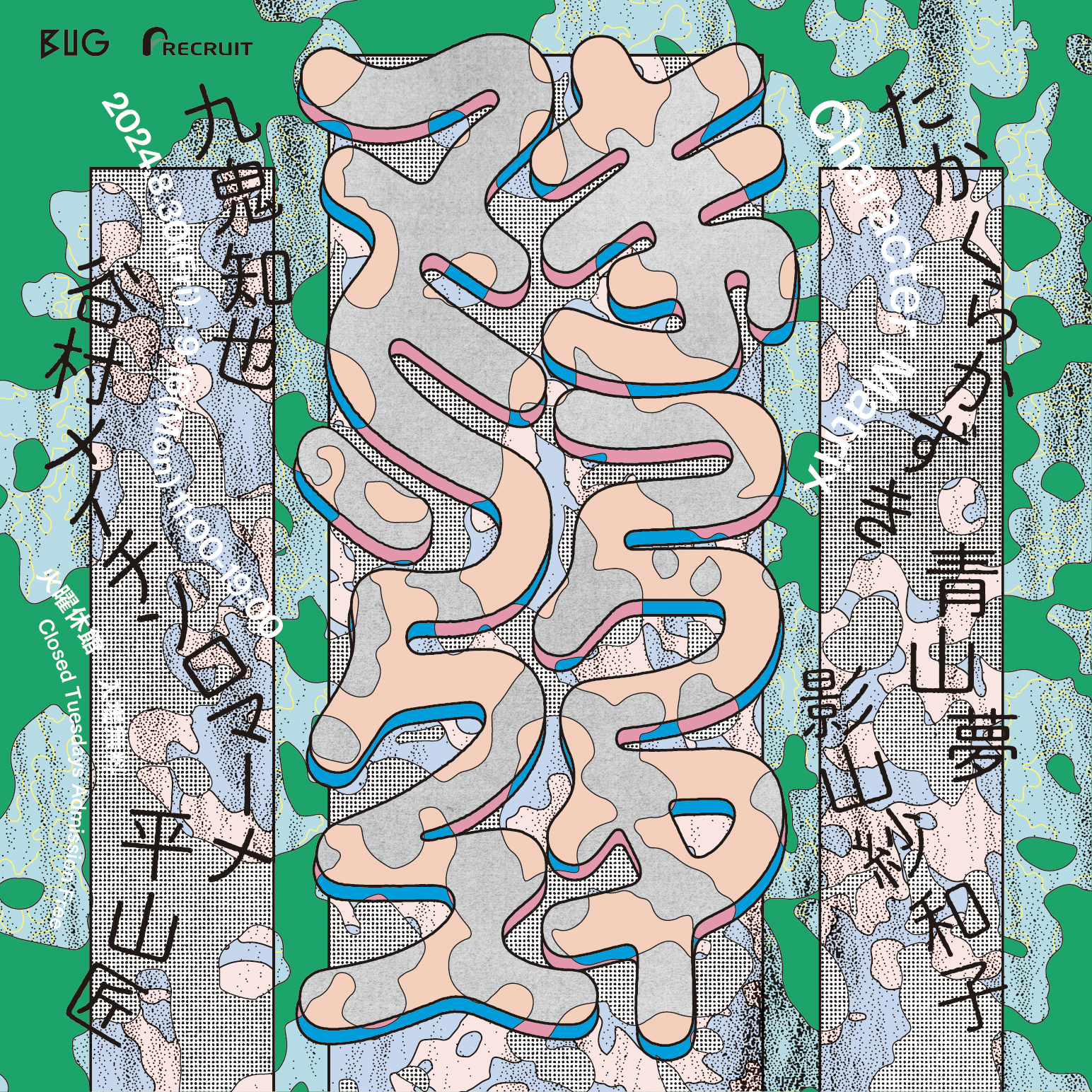

For the group exhibition Character Matrix (a collaboration with BUG), the artist Kazuki Takakura, who was born in 1987—just at the right time to have experienced this period of transition—worked with artists born after him, in the 1990s. The exhibition reveals a mythical foundation on which the countless characters they have encountered are transformed, exchanged, and merged together, dissolving into one another. Interestingly, the exhibition space is designed in a way in which mythical characters from medieval Japan and Asia coexist with characters reminiscent of contemporary anime and video games. Here, a compact universe is formed through the correlations between characters who bridge the present and the past, resembling a mandala from esoteric Buddhism that contains the deities and cosmology of the Mahayana tradition. What immediately strikes us is that these characters have transcended their respective standardized stories (contexts) and taken on lives of their own, becoming elements that transform and expand the (hi)stories of each individual artist.

This situation evokes the ecosystem of digital games and anime of the Heisei Era (1989–2019) as it broke away from the analog ecosystem of the Showa Era (1926–89)—or of the world of manga and character toys that inspired those games and shows. The exhibition space, which is designed for visitors to wander around, is surrounded by Tomoya Kuki’s 108 ceramic figures, as though they were yōkai (ghosts and demons) or protective deities. In Sawako Kageyama’s video works, television screens display news and weather reports as part of “Nyan-tere” (Meow TV), which brings to mind internet memes of the Heisei Era. Along the stairs and the walkway on the upper level, Yume Aoyama’s fluffy three-dimensional canvases depict an entire hybrid universe in which the digital and the analog mix, while Romana Machin Tanimura’s works made from urethane foam hang wrapped in vinyl packaging, like a prize at a fair or something hanging from the eaves of a countryside toy store. Takumi Hirayama’s large-scale work Hanira, which is made of cracked clay, towers over this world full of characters, like a Studio Ghibli film or a kaijū from a tokusatsu show; water is periodically sprayed onto it, and this wet-damp rhythm surfaces the materiality of the earth-based material that is clay.

As is strikingly apparent in Hirayama’s sculpture, this vision of things is not situated in the realm of ideas, but puts to the visitor the question of what it means to always care. Buried within the venue is a separation between an exoteric space presented across the upper level and an esoteric space concealed on the lower level, as if this were an esoteric Buddhist temple. Switching between several viewpoints like a character in a video game, the visitor advances and, before they know it, moves from the dry realm of the upper floor to the damp inner realm. There, the visitor experiences the artworks, which form an invisible context as yorishiro (vessels for spirits), from point-blank range, as if they are peering in, or viewing them as passing scenery; at the same time, with a telescopic/bird’s-eye view that evokes a mandala or the illustrations on ahandscroll, they become aware of their own spirit moving through this world. Thus, while encountering the ludic bodies which we could describe as the artists’ alter egos through their respective works, the visitor, without realizing it, transcends all these dichotomies—man/woman, sacred/profane, life/death, present/past, material/spiritual—and is once again confronted with a material dimension that precedes the birth of these characters.

Each artwork’s world percolates out from the venue and into the online space. Through a new manga available as a PDF, the artists create an interconnected character universe, and exchange unconscious memories and stories. It is also worth noting that in this exhibition, the viewpoints of men and women artists share a desire for objects and their commutativity on a profound level. Throughout the exhibition space, one clearly detects an interest in characters as they are before they are differentiated according to gendered notions of male/female, as well as the energy of a polymorphic and monstrous drive that precedes the play-acting that children engage in as though replicating their parents’ relationships. The space is brimming with an energy that doesn’t fit into the fixed aesthetic frameworks surrounding men’s post-pubescent sexual desire and their gaze regarding the opposite gender; the gender identity of women, who have internalized this; or deviations from such notions of gender. This energy transforms the rigid norms and received ideas that adorn subcultures.

***

Let’s return to the exhibition. I started walking along the corridors, slopes, and stairs that serve as its stage setting, as if entering a game on an LCD screen. There, I came across a group of works that clearly reference the history of characters in the early Heisei Era; following the thread of my imagination, I was led to an immersive experience not unlike a tainai-kuguri (a ritualistic passage through a womb-like space) in a corridor of hell that resembled a realm from medieval esoteric Buddhism. In this strange space, I ended up wandering around like a child who has strayed into a religious festival or a temple precinct at dusk. This approach to exploring the space stands in contrast to a certain kind of educational game, in which the player develops the character based on predetermined paths and norms: here, there is no way to predict what one will encounter or which dangers one will face. Along with this unpredictability, this exhibition reminded me of being on a promenade—rather like one of those well-made games in which you travel across an unsettled world open to friend and foe alike.

Entering the corridor section downstairs, I felt a noticeable change inside my body. Minutely detailed works by Takakura himself, Neo-Wayan -Kala- and Kaya-sen mandara, were displayed in the deepest part. However, this does not mean that the exhibits have been arranged according to a hierarchy centered firmly on Takakura. If anything, in this exhibition Takakura’s works are anonymized and mixed in with the rest to the extent that they can no longer be distinguished from the characters created by the other artists.

Through this multilayered structure which combines the exoteric and the esoteric, the stories (contexts) behind each character seamlessly link together, and the psychological worlds of Takakura and the other artists appear to be assembled into a single, complete universe. Within the venue we notice a clear and concise totality that transcends generational and gender barriers. However, rather than presenting a dramatic narrative built around specific themes or concepts, it is akin to a fine patchwork of imagination that has been stitched together through many random circuits, making visible an energy that precedes the images and has no fixed form. While clearly referring to the industrial system of contemporary Japan that encourages the purchase and consumption of “character goods” aimed at specific genders and age groups, this energy is actually in critical tension with the capital driving this tendency, and is aimed at deterritorializing the mythologized image of characters.

Japanese manga and anime movies since the end of the last century have astutely reflected the changes of an age that, above all, has sought to replace the heavy/thick/slow infrastructure of the analog world with the lighter/thinner/faster organizational capability of information processing. What is interesting is that, now, the generation of young people born in the 21st century and known as “digital natives” are retracing the roots of the imagination that arose in the analog culture of the Showa and Heisei Eras, and tapping into the deep vein of characters linked to Asian religion and mythology to find methodologies for creating their own worlds. And many artists are using thick, sticky mud or slime, or fluffy or coarse haptic media, in order to radically interrogate the relationship between fantasy and reality. Characters transcend their symbolic contexts, expanding the realms of their particular images on a material level. They range between multiple stories, while transforming the contexts of the stories that birthed them. Here, the foundation (womb) from which the characters are born is the very material/symbolic environment that surrounds them; in this exhibition, it is as though the characters themselves, so as to evoke their environment, are trying to return to a material tactility which we can call “slime-mold realism.”

This tactility makes us think of the faintly nostalgic world of noise and bugs—not the same thing as the potential for serious system errors and crashes contained within the sleek, well-oiled information environment of the 21st century (where everything advances smoothly and rationally). Much like how Nam June Paik’s work, for example, simultaneously addressed the techniques of Buddhist meditation and the state of consciousness that comes with being pulled into information media, the world of Character Matrix encompasses certain kinds of spiritual techniques developed by Asian religion and mythology, as well as the feel of a certain variety of noise and chaos that has become part of our everyday lives. This is not about, for example, banishing certain kinds of malfunctions, obstacles, or delays, rendering them impossible; rather, it actively incorporates such detours and suggests an anarchic stance of resistance, drawing on the wisdom of animism and the East, against the speed and smoothness that result from large-scale capital investment. This is a statement of protest against the use of high technology to manage one’s state of mind, based on a new kind of solidarity that marries low-tech play and AI tools; a resistance, rooted in rough materials and slowness, against the smooth, fast flow of information.

What emerges from this exhibition is not a panoptic narrative structure that aims for a full understanding of the world, centered on the privileged characters that feature in it; it is instead the manifestation of a wild kind of thinking that deploys characters as anarchic, pantheistic yorishiro in an attempt to disrupt the systems and structures of storytelling, materially dismantle smooth systems, and return images to a plane coated with material noise. We can consider the subjects in esoteric Buddhism (the ascetics, the supplicants) to be the forerunners of Character Matrix, in the sense of closing in on a matrix of animist and Buddhist deities through an ascetic’s subjectivity and becoming a living yorishiro for those characters. Moreover, in dismantling these characters (deities) and returning to the great matrix (the Womb Realm) that is nature, the slime-mold-like character of this exhibition calls to mind the multidimensional thought process embodied by Minakata Kumagusu. Just as Kumagusu saw the material sphere through his mandala-thinking, so this exhibition provides a vivid portrayal, through its individual works, of the melting down and recasting of materials—plastics, rubber, glass, silicone, rare minerals, etc—that backdrops today’s information environment and toy industry.

When considering the dimension of forms, which serve as archetypes, Plato also posited a space that must first exist in order for them to be formed, which he called khôra (χώρα). It is in this same realm that characters are born. Characters always appear on the membrane-like border where the material meets the spiritual or nature meets culture, becoming the objects of play and prayer. Then, eventually, they break and are disposed of, collected, melted down, then seek transmigration back to the capitalist marketplace. This exhibition considered the origin of games and characters, looking for the realm of materials that are rough, slippery, fluffy, and thick. Was it not a rare attempt to critique a capitalist realism that rejects a return to the Earth’s environment and to bring us back to the original field: our heart, our spirit, as Homo sapiens? In other words, we could even say that Character Matrix shows us “another nature”: one where our hearts belong, and to which the yorishiro are heading.