Exhibition review "Polyparole" a solo exhibition by hayate kobayashi

Polyparole, a solo exhibition by hayate kobayashi, an emerging Berlin-based artist who graduated from Tokyo University of the Arts and Berlin University of the Arts, is on view at BUG in Yaesu until July 21. The exhibition draws from the artist’s experience studying abroad during the pandemic, as well as his self-awareness and circumstances as a long-term immigrant and zaigai-hōjin (a term referring to Japanese nationals living abroad), reflecting the emotional complexities of being in an ambiguous position as an international student.

A number of video works come into view upon entering the exhibition space, and we experience an interplay of voices coming from the works. Perhaps you’ve walked through the streets of London or Berlin, down a boulevard where various languages fly back and forth—countless voices get closer, then farther, then closer again, only to drift past. As soon as I entered the exhibition space, such memories came flashing back. The individual works, which were seemingly self-contained, transcended their boundaries to emerge as a single “noise” that permeated the entire space—perhaps this is the “polyparole” that the artist is referring to. In our daily lives, we rarely pay attention to “noise.” However, if we listen carefully, each noise contains a voice. The experience reminds us of the presence of someone’s voice, whether loud or quiet, clear or indecipherable.

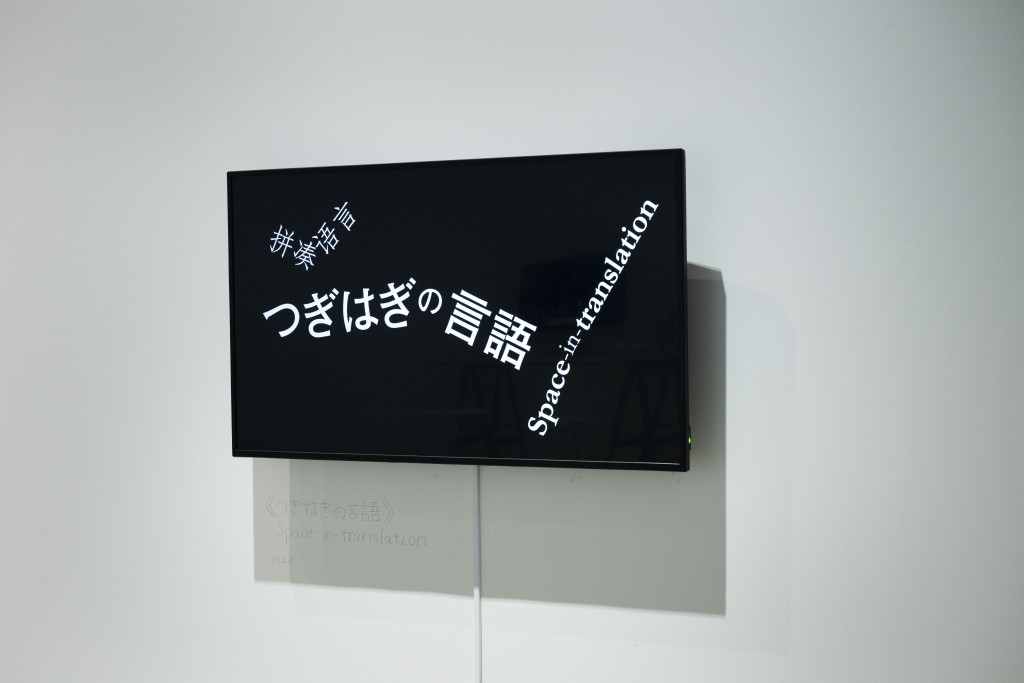

kobayashi seems to broadly classify his works into two categories: “large works” that deal heavily with social issues, and “small works” that are more personal. In this exhibition, To all the 1,344,900 mouth and Space-in-translation fall under the category of “large works,” while the podcast series Süß and dailylog are “small works.” Recorded at various hours and places, dailylog is a video piece in which Kobayashi relays trivial details of his life in Germany, as well as the distressing and frustrating experience of studying abroad during the pandemic. I related deeply to his musings in the video, since I also study abroad in the UK. Many of the things he mentions (such as the short winter days and the lack of a bathing culture) are not just specific to Germany, but common across Europe. He also touches on a kind of association game where he substitutes things seen in Germany for something in Japan (for instance, “This view looks like the Tama River”). This reminded me of how I’ve also managed to process my homesickness through such ruminations.

I’d like to consider the title of the exhibition, Polyparole. “Poly” is a prefix meaning “many” or “multiple,” while “parole” is a French term generally used in the field of linguistics. According to the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, language as a general phenomenon (langage) has two components: langue, which refers to a system of social institutions and rules that supports the linguistic activity of people who share the same language; and parole, or the use of words by individuals based on the social institution of a langue. Simply put, “parole” is the individual act of speech (chitchatting).

However, much of the media we are exposed to, such as signage on trains and YouTube videos, has been stripped of the natural and human qualities of conversation, prioritizing a more direct transmission of information. Breaths and filler words (such as “uh” and “like) are considered unnecessary and are often edited out before reaching us. This process is nothing more than an attempt to remove the inevitable noise produced when langue is utilized as speech by an individual, resulting in what I would like to call “dehumanized speech.” But Kobayashi’s dailylog and Süß counter this approach, preserving the incredibly familiar aspects of human speech that are absent in dehumanized speech, such as long periods of silence, the artist’s breaths, and filler words. This felt a bit strange to me, but paradoxically, I think it made me aware of the prevalence of dehumanized speech within our media landscape, and the abnormality of how I had become accustomed to it.

Returning to the topic of linguistics, perhaps you have heard that butterflies and moths are differentiated and recognized as separate creatures in Japanese, while both are called papillon¹ in French. In other words, the signifié (signified) that a signifiant (signifier) refers to fluctuates even between languages.² For example, it is extremely difficult to translate the Japanese phrase otsukaresama [お疲れ様] into another language while maintaining its nuance. It is a unique greeting that neither “good job” or “thank you” encapsulates. In fact, we see examples like this across the world (or more precisely put, all languages likely have this quality), and many of Kobayashi’s works utilize this untranslatability, such as in his use of multilingual subtitles in Space-in-translation. Indeed, it can be said that Kobayashi succeeds in capturing the fluctuation of the signifié across languages through the medium of moving image.

*¹ More precisely, butterflies are called papillon and moths are called papillon de nuit.

*²I write “even between languages” since, technically, the signifiant of a signifié can fluctuate between individual people as well. However, since I am referring only to fluctuations that occur between languages and not between individuals, I abbreviated my explanation.

Dann Kurauchi was born in 2003 in Tokyo, Japan, and received a Foundation Diploma in Art and Design from Central Saint Martins, University of the Arts London in 2022. That same year, he received a scholarship from the Ezoe Memorial Recruit Foundation, and has since been studying at the same school, majoring in Fine Art (2D). Working across mediums including painting, sculpture, and video, he adopts a decentered approach to his practice, attempting to disperse his desire for production in various directions.