Confronting Technology Beyond One’s Control: On Shiho Yoshida’s Vestiges of the Unseen

In Shiho Yoshida’s solo exhibition, Vestiges of the Unseen, she presented new works focusing on images that result from various unexpected errors caused by printers, cameras, and the internet. Rather than using typical photographic printing methods, she displayed a large quantity of offset prints, alongside the plates that were used for printing them. Offset printing is the most common method for producing commercial material such as newspapers, magazines, and flyers. When I saw the announcement for the exhibition, it intrigued me that Yoshida, who is part of the generation of digital natives, had chosen to present her work in the form of printed matter, which is a format that could be considered quite analog (while still being prevalent today). If we look back on contemporary art through the lens of print, there were a number of artists in the 1970s who used material like newspapers and advertisements to create works of social critique. Is there a kind of critical perspective on the current state of media in the works in this exhibition? I will consider this at the end of this essay, but first I would like to describe what was on display.

The two themes reflected in the Japanese title of the exhibition, Insatsu to Yūrei (Prints and Ghosts), each originated from separate interests. Yoshida’s curiosity around printing technology was sparked when producing her photo book, Survey: Mountains (2021, T&M Projects). Struck by the crispness of the ink and the comparatively high-resolution printing data required for offset printing, she began to consider the idea of an exhibition that dealt with printed matter. Yoshida’s observations on modern society led her to the theme of ghosts: she felt us to be in in an era of growing interest in uncertain things, as evidenced in mockumentary, a genre of fictional films that use documentary techniques, and viral phrases like “liminal space,” a term used to describe environments that are removed from reality. She also learned that in the photography industry, “ghosting” refers to lens flares (shapes and dots that appear when a strong light source like the sun enters the lens), and that in the printing industry, there is a phenomenon wherein ink density varies in ways not reflected in the data. She began to see these unexpected images created by machines as something ghostly, and with these interests in mind, she developed a concept that combined printed matter—a kind of apex of material presence—with uncertain and ambiguous phenomena.

There are three main phenomena that Yoshida chose to explore in her images of ghosts. First, lens ghosting: to capture these aforementioned lens flares, Yoshida used multiple lenses to photograph a mountain landscape. Traces of light in the forms of lines and dots can be seen in these landscape photographs. Second, ghosting that appears on Google Maps. These are errors that often occur when multiple satellite images used to construct these maps are combined. Photographing a computer screen, Yoshida captured a massive shadow shaped like a submerged ship that appeared in a port of Izu Ōshima, which had caused a buzz on the internet a few years ago. She also rephotographed this image projected onto a plant, and the results are included in the installation. Third, images of a so-called “liminal space,” a term that I introduced earlier. The word “liminal” describes something that exists at a threshold or boundary, and is also used when describing the border line between what can and can’t be perceived. When used in conjunction with “space,” it describes an ambiguous place that lies between reality and unreality. Yoshida used photographs she had previously taken of hallways and interiors of buildings that have since been demolished and no longer exist, and incorporated them into the exhibition as her own interpretation of liminal space. She also rephotographed these images projected onto the surface of water. A distinctive aspect of these ghost images are that they result from phenomena generated by machines or the internet, and do not feature a single human-like ghost. It seems that Yoshida is mainly interested in how to come to terms with the uncertainty that is generated by technology rather than by humans.

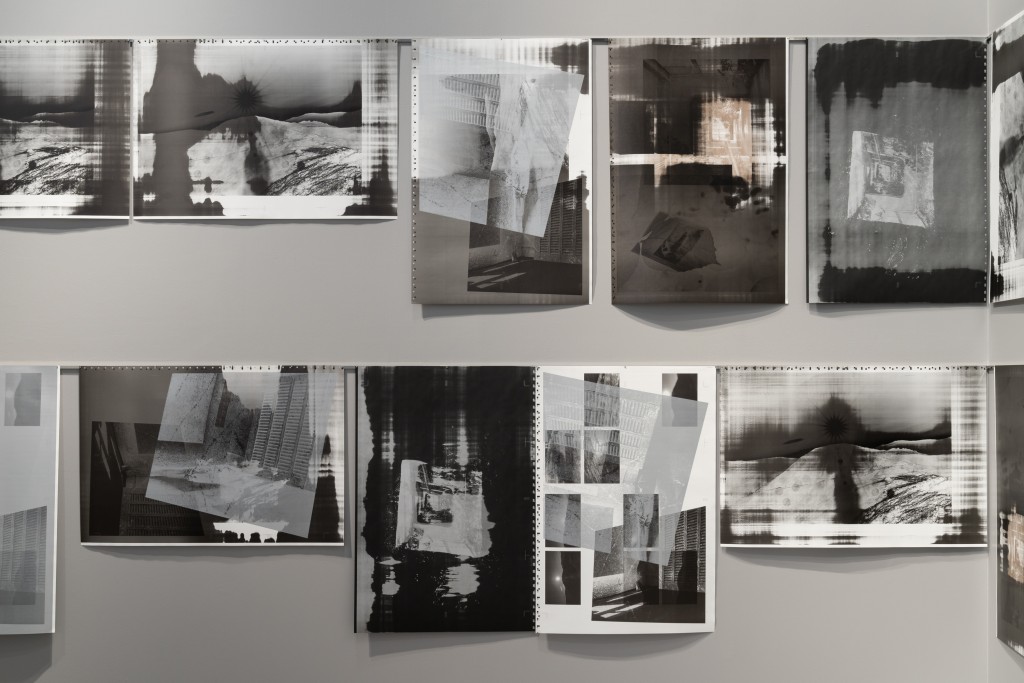

While Yoshida photographed and selected images herself, printing was done in collaboration with Toshiki Koike, who participated in the exhibition as art director, and LIVE ART BOOKS, a printing company. The exhibition featured approximately 10,000 large-format prints and several aluminum printing plates, which were used in the offset printing process. Each plate was framed and displayed with the prints, as objects of equal importance. Around 40 printed sheets of paper were placed along the walls, held in place with magnets on a rail. When viewed individually, the printed registration marks and color bars are apparent. There seem to be plans to make a photo book with these prints. They were also used in the exhibition flyer (along with additional text). One highlight of the exhibition was being able to see a set of reproductions change format depending on their use: works on display, photo books, or flyers.

The rest of the printed material was displayed as-is, straight from the printing press, placed around the space on pallets in stacks of roughly 3,500 sheets. The sides of the stacks of prints, which show ink bleeds produced by printer errors, are particularly eye-catching. While printers are characterized by their ability to mass-produce identical copies all at once, by making adjustments to the machine, a different image is produced on each and every sheet, as evidenced by these random stains. In other words, the ink intervenes on each photograph in ways beyond the artist’s control. However, looking at the prints on display, you do not get the sense that these deviations are violently destroying the photographic images. Instead, the ink itself is ghost-like, adding another layer to the work by overlapping with the other ghost images.

Going back to the topic of printed matter in art, which I touched upon earlier, one example with a focus on printing errors that came to mind was the photographic work of Sung Neung Kyung, a pioneer of the avant-garde in South Korea. For example, in Venue 5 (1981), he collected and copied photographs in newspapers that had failed to print completely, and created a work by painting over lines created by the un-printed areas. The work was also an indictment of the popular control of the state, which had permeated even the mass media.

The critical aspects contained in Yoshida’s work, then, lie in her transformations of the errors and inconsistencies produced by technology into art, presenting a new perspective on our coexistence with the inexplicable. Phenomena that transcend understanding also serve to fascinate people today, as made apparent by the various ghosts contained in the work. Prompting insight into the state of society is one of this installation’s critical messages. Hiroki Yamamoto writes in an essay included in the photo book Survey: Mountain, “By taking photographs and arranging them as installations, Yoshida confronts an ambiguous world.* ” The exhibition was an opportunity to renew this method of giving shape to the world, this time through printed matter. I am looking forward to seeing the continued evolution of Yoshida’s exploration of her medium.

* Hiroki Yamamoto, “Yama wo hakaru, sekai ni katachi wo ataeru—Yoshida Shiho no Sokuryō: Yama shirīzu ni tsuite (Measure a mountain, give shape to the world—On Shiho Yoshida’s Survey: Mountains series),” Survey: Mountains, (T&M Projects, 2021), p.64