Words are not only written (écriture) but also voiced (parole). Nowadays, we read copious amounts of text via our smartphones, always on hand, and listen to many voices through videos and podcasts. It’s interesting how the pandemic prompted many people to (once again) listen to audio media, such as podcasts and radio shows. While audio media is conducive to multitasking, its increased popularity may have been a reflection of people’s desire to feel the presence of someone distant. Compared to printed text, which is standardized under a specific font, edited, and fixed, the human voice is much more dynamic and lively, revealing the utterer’s singular body.

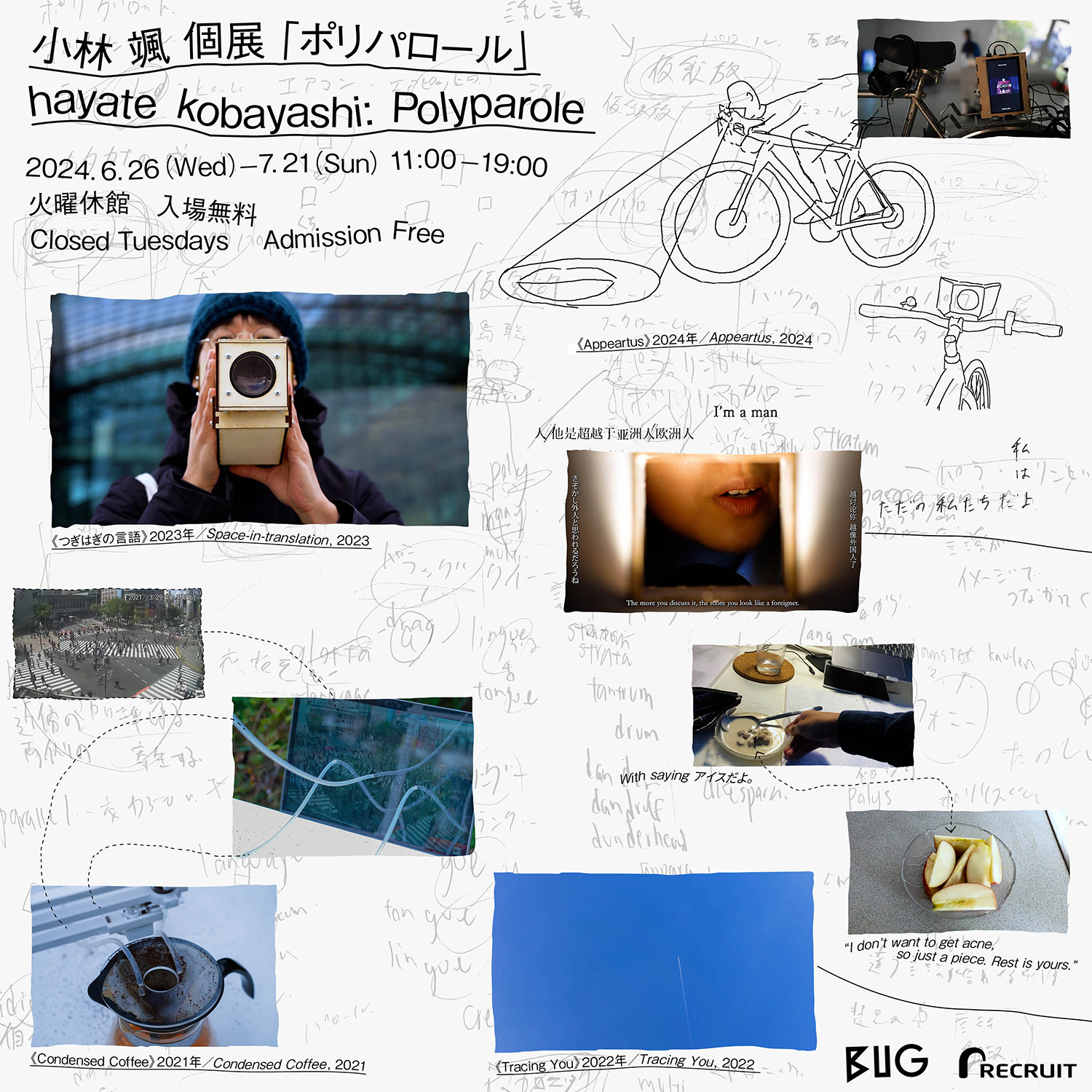

In Hayate Kobayashi’s solo exhibition Polyparole, the Japanese artist uses such voices in multifarious ways to represent his personal process of exploring the linguistic aspects of his stay in Germany. It is worth noting that, even though the exhibition focuses on documenting his time there, it does not feature any German people or the language. It rigorously highlights the artist situated outside of his mother tongue as well as other Asian immigrants and students studying abroad (and Japanese people living in Japan), bringing the “outsider” into sharp relief.

“Exophony” is a word that connects the artist living in a foreign country with exiles and foreigners that he encountered there. While the term points to the literary practice of writing in a language that is not one’s mother tongue, in Japan, it is well-known through Yōko Tawada’s homonymous book, in which the writer expansively defines it as “a state in which one exists outside of their mother tongue.” Tawada’s broader understanding feels fitting given that the Greek word phonos, meaning voice or sound, is better suited to describe speech than writing. We also see this interpretation in the exhibition title, Polyparole, or “multiple utterances.”

Kobayashi sees his life in the foreign country of Germany as one in a state outside of his mother tongue and has made several works on the topic. In this exhibition, he also included Tracing You, a work that explores the sensation of not easily fitting in with social norms, even as a native speaker in Japan, and Exophonifesto #1, a video piece that evokes the friction that occurs when reading out the words of an English-language writer that have been translated into Japanese. When considering exophony, it raises the question of what the opposite state would be, in which one “exists inside their mother tongue.” Of course, the answer is not as simple as “when one is using their mother tongue in daily life,” given that many of us live as foreigners even in places where we speak our mother tongue.

When we play around with the etymology of the word “exophony,” the antonym of the prefix “exo” (outside) is “endo,” producing the word “endophony” when combined with phonos. When I looked up this word, I learned through the few search results that it is sometimes used to describe “inner speech.” Although it is a voice that others cannot hear because it doesn’t physically ripple through air, it clearly rings in one’s consciousness—a voice that is close to one’s raw and undifferentiated core, rather than an abstract concept such as “a country in which one speaks the mother tongue.” In this sense, the many “chitchats” that comprise this exhibition seem to let the viewer listen to the inner speech of Kobayashi himself and his interviewees. Or perhaps it’s more precise to say that the artist shows his attempt to close in on these people’s inner speech. Rather than works of artistic expression, the acts depicted in his work—tracing the contours that appear in the home videos of strangers’ families, or filming himself reading a Virginia Woolf novel aloud in various locations—seem like gestures through which he observes their influence on him and his subsequent unexpected reactions. The acts seem to bring out his repressed inner speech by deviating from the norm.

However, in Space-in-translation, the centerpiece in this exhibition, Kobayashi filters words spoken by another person in a different language through the process of translation and uses them as the basis for his poetry. He interviews Liao Yiwu, a poet exiled to Berlin, who responds in Chinese. From there, he uses machine transcription and machine translation to turn the words into English and creates a multilinguistic poem as he discusses its contents in English with another Chinese friend. This act of translation that eschews the idea of an “accurate translation” from the start, instead aiming to incorporate the artist’s own reception and interpretation, seems to be an attempt to connect these words outside of his mother tongue to those that are internal to him.

What is most intriguing is how the artist uses various tools in his series of linguistic experiences. A mask-shaped device, which only lights up and displays the speaker’s mouth when they vocalize, appears in several works in different ways. In To all the 1,344,900 mouth,, he uses the device to show his mouth glowing from the mask’s interior, and also to project a video of his mouth onto a surface. In the former usage, if the uttered voice is the focal point, the speaker’s mouth is emphasized by the video and synchronized audio. The latter usage—in which the mouth is displayed on physical things outside of the body, such as trees, walls, or the ground—evokes a strange feeling, as if the spaces are possessed by the voice. In Appeartus, the artist speaks continuously as he rides a bicycle while wearing a voice-triggered apparatus that projects light from his mouth . The piece reminds viewers that the act of speech is a kind of “bicycle operation,” or something that must keep going in order to not collapse. When we speak, we do not plan out our every word. We merely utter words as if digging them out from our body, relying on the faint light that emanates from the previous one amid total darkness.

This new and peculiar device is a component of the artworks, but more importantly, it triggers an interaction with the human user. What kind of sensation does it provide the speaker? New tools serve as mediums that, more or less, constantly reshape our everyday life, and the act of making such tools connote certain intentions and expectations. I cannot verbalize the logical reason behind why Kobayashi created such a tool in a foreign country during the pandemic. However, contrary to common belief, the act of creating a new tool is itself an illogical one to begin with. To go against norms and standards, create and sustain new sensory and perceptual experiences—based on a feeling of unease with the surrounding world—is an extremely aesthetic act. I was left eager to learn how these tools, which Kobayashi (presumably) created out of necessity, influenced him during the process of making and using them.

In this way, I see Polyparole as more than a series of completed artworks. By presenting traces of the artist’s process of living and responding to his experience of exophony, the exhibition offers viewers various insights into their own linguistic aspects of life. I also grew up having exophonic experiences as a polyglot who speaks Japanese, French, and English, and never had a defined mother tongue. In this way, my impression may be quite different from someone who feels as though they have a single native language. Even so, I felt an emotion similar to a prayer, hoping that more people can feel the possibility of queering even their mother tongue.

Dominique Chen is a ferment media researcher with a Ph.D. in Interdisciplinary Informatics. Co-founder of Dividual Inc., and a former researcher at NTT InterCommunication Center [ICC], he is currently a professor at the Graduate School of Letters, Arts and Sciences at Waseda University. He is the founder of the interdisciplinary research group Ferment Media Research, where he researches the relationship between technology, humans, and more-than-human beings, and develops Nukabot , a fermentation robot that can communicate with humans and microorganisms. He is the author of numerous publications, including Words that Create the Future: To Connect the Unintelligible (Shinchōsha).